Note: I wrote this five years ago for a blog and it was even published in The Prairie Times in the September 2019 issue. Since today is the 80th Anniversary of D-Day, I thought this would be the perfect article to post in honor of it. God Bless the Greatest Generation!

~*~

Growing up, I heard my grandfather fought in WWII, but as a kid I really didn’t know in what capacity. My family knew the basics: he was in the ETO; at various points he was in Iceland, England, France, and Germany. He had medals and he was involved with the gliders. He rarely spoke of his service and on the off-chance he did, he was vague. On the 50th anniversary of June 6th (June 6, 1994) my grandfather was in the nursing home and his younger brother Allen came to visit him. The whole family was there.

Allen made an off-handed comment to him saying, “Well, Bud, you know where we were fifty years ago today.”

“Yeah, D-Day.” And my grandfather began to cry.

Nothing more was said.

Everyone knew better than to pry too much. He avoided flying and planes, and later in life, he suffered PTSD. When he passed, his secrets and experiences died with him. A couple of years later, the miniseries “Band of Brothers” was released and it renewed my family’s interest in Grandpa’s service in WWII. We went through his papers with a fine-tooth comb, rediscovered the medals and patches, and that he had both paratrooper and glider wings. Uncle Allen filled us on a few things. We were able to piece together a little of his story. Then, thanks to the internet, we were able to learn exactly what the gliders were and what their function during the war.

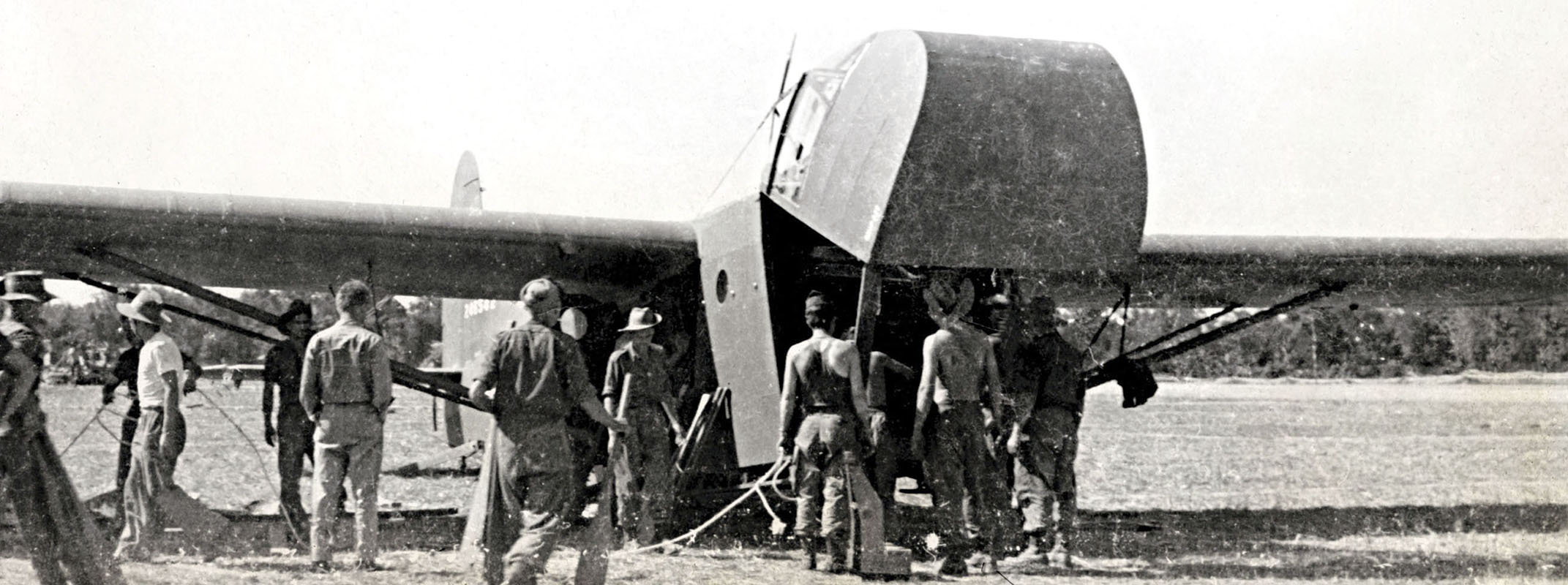

The Germans were the first to use the gliders, in their invasion of France. In response to the German’s success, both America and British created their own versions. Nicknamed the “Flying Coffins,” a high-wind cabin aircraft, the gliders’ framing consisted of plywood and sometimes aluminum, and they were covered in canvas fabric. The glider would be connected to a C-47 aircraft, via a cable, and when both were air borne, the glider would be towed behind, “gliding” along. Without an engine and propellers, it flew silently and undetected by the enemy. The men, the “glider riders,” on the other hand, insisted it was extremely loud inside.

Depending on the type of glider, it would either be transporting fifteen men, or supplies, jeeps, and other equipment. When the glider was near its LZ (Landing Zone), it would be detached from the C-47 and it would crash land. Yes, you read that correctly: crash land. The survival rate wasn’t promising. It was suicidal, really. The glider pilots would have to navigate the engineless aircraft best they could, avoiding trees and stakes that had been erected by the enemy. Hopefully they’d land somewhere near the LZ. The gliders would also be under assault from the Germans. One testimony I heard was of a glider rider awaiting the glider’s detachment from the C-47, he was stunned when the laces on his boots suddenly stood on end. Numb from the adrenalin coursing through his veins, he later learned he had been shot in the foot. Following the crash landing, if the men survived, they would climb out of the glider and immediately enter into combat. Uncle Allen once told us that he had considered joining the airborne and asked my grandfather about it. Grandpa dissuaded him from it. He thought it was too dangerous for his younger brother.

The gliders were used in many major airborne operations throughout WWII: the invasion of Sicily, D-Day, Operation Market Garden, Operation Varsity, and in Operation Thursday in the Far East. In the various operations, the causalities were heavy. The gliders were instrumental during the war, and the glider riders proved themselves over and over again.

After WWII, the gliders were discontinued in favor of the helicopter. In comparison with the paratroopers, the glider riders involved were largely forgotten. There are books out there for those who want to do more in depth research, but more often than naught, the gliders are relegated to a footnote in the history books. Or a small mention on a documentary.

Looked down by many, including the paratroopers, they weren’t issued jump boots, and it wasn’t until July 1944 that they “earned” their right to wear glider wings and receive hazard-duty pay. During WWII, eventually most men were drafted into the military, but to be a “glider rider,” it was voluntary. The strongest and the best persevered against all odds. Why and how could these young men – including my grandfather – do such a dangerous, and in many cases, thankless job?

In my opinion, only the deepest and strongest patriotism could have emboldened them…Along with the fact that they were young and away from their homes for the first times in their lives. The gliders were something relatively new, untested, and risky. It was an adventure like no other and in the end the young men played their part in fighting against evil.